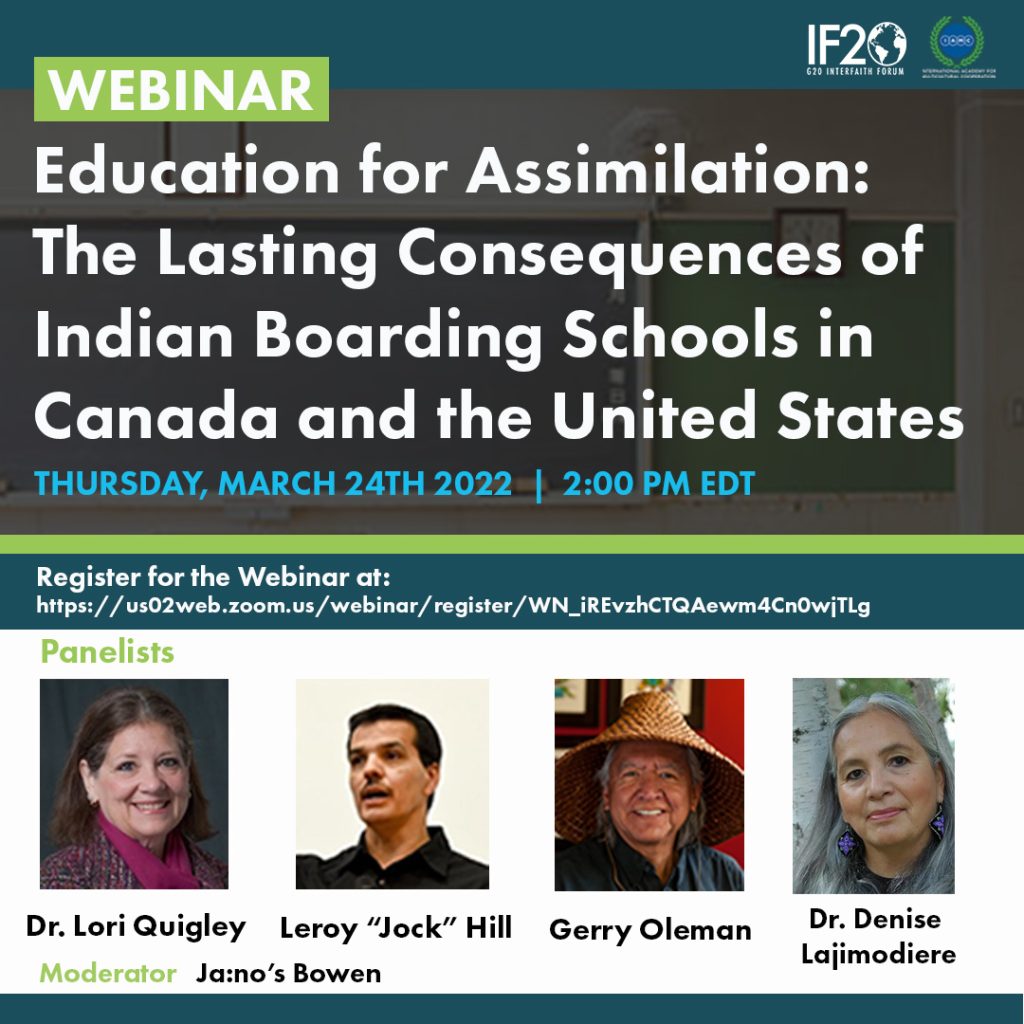

On Thursday, March 24th, the G20 Interfaith Forum held its third webinar of 2022, organized by its Anti-Racism Initiative and co-sponsored by the International Academy for Multicultural Cooperation. Panelists included Dr. Lori Quigley, Citizen of the Seneca Nation and Member of the National Advisory Council on Indian Education; Hohahi:s-Leroy “Jock” Hill, Member of the Cayuga Nation and Bear Clan, Professor of Indigenous Knowledge, and Cultural Advisor; and Elder Gerry Oleman, Citizen of the St’at’imc Nation of Tsal’alh (Shalalth B.C.) and Change Agent for First Nations communities. Ja:no’s Janine Bowen, Citizen of the Seneca Nation and Director of the Seneca Language Department, Allegany Territory, moderated the discussion. View the video recording of the webinar here.

Audrey Kitagawa, Chair of the IF20 Anti-Racism Initiative, began the discussion by introducing the purpose of the G20 Interfaith Forum and the focus of the discussion. After introducing each of the panelists, she gave the floor to Ja:no’s Bowen to moderate.

Hohahi:s-Leroy Hill offered words in the Seneca language to bring the hearts and thoughts of participants together on the topic at hand, then Ja:no’s Bowen provided more context around the webinar’s theme: The consequences of Indian Boarding Schools in the U.S. and Canada.

“While most Indian Boarding Schools have closed their doors, the effects of years of trauma linger in Indigenous families and homes. They continue to impact the wellbeing of Indigenous communities—in the form of mental health issues, suicide, violence, addiction, and more. In order to take action toward creating education systems that respect Indigenous cultures and religious traditions, we must first acknowledge that both governments and religious institutions played a major role in the literal and cultural genocide of these communities.”

Bowen then invited each of the panelists to share their experiences and thoughts on the topic.

Elder Gerry Oleman

Oleman began by explaining that he’d spent 13 years accompanying residential school survivors through criminal courts in Canada, and through that had been able to experience the consequences of the schools firsthand. He and his mother both also attended residential schools.

As part of the strategy of assimilation and cultural genocide pursued by these schools, Oleman said getting rid of mother tongues was critical.

“My mother’s first language was literally whipped out of her. I resented my parents for not teaching me their language. But when I heard about what happened to her at age six, I forgave her. She was protecting me, because she knew that I would eventually attend a residential school as well.”

As language provides important cultural ties and rites, Oleman said killing a language almost kills an identity. Many today wonder “am I Indigenous enough” because they don’t speak the language, and they lack a connection to their heritage and community. He said that in place of the identity of language, a new identity was created for, pushed upon, and internalized by a generation of children: that of the stupid, savage, drunken Indian.

“There’s been a massive wounding or trauma of all Indigenous communities across Canada and the U.S. It’s like a cookie cutter: suicide, addictions, violence. And the numbers keep rising. We need to ask why.

“It’s because of what happened to us as Indigenous people. We’ve all been wounded by racism, religion, reservations, residential schools, and more. But because this is a man-made problem, we can fix it. We still have the rituals, practices, and knowledge in our communities to heal ourselves and make ourselves strong.”

Dr. Lori Quigley

Quigley focused her remarks on the research she’s done on Indian Boarding Schools and their effects. She said she began her research not as an academic, but as a Seneca Mother trying to figure out how her community got to this space of trauma. Most of her research involves finding the case files of those who attended Indian Schools during the 160-something-year period during which they were common.

“The boarding school represents American Colonialism at its most genocidal. … These schools relied on national and local police to abduct children and take them from their parents. We have generations of children who were forcibly taken from their families.”

Quigley added that Indigenous people were valued at nothing unless they got a Westernized education, and despite once being a classroom teacher, she believes we’re doing huge damage to our Indigenous communities in our schools. Native students aren’t respected or acknowledged for who they are as Indigenous children.

She ended with a reminder that the horrors of Indian Boarding Schools are not just about the children who died there:

“When we first started hearing about the children buried in unmarked graves at these residential schools, we were shocked and devastated as an international community. But we must also acknowledge that there are still survivors of that among us today. My mother, who has dementia, still dreams of those abuses that happened to her 80 years ago as though they happened last night.”

Hohahi:s-Leroy “Jock” Hill

Hill began his remarks by reminding the audience that the issue at hand was one of many layers that must be unpacked and dealt with one at a time—but that we’re starting to move in a positive direction, striving for the revitalization, renewal, and survival of Indigenous people.

“Our ancestors were masters at that. It’s a gift from our creator: to survive and to be survivors. We are survivors.”

Hill told the story of his grandfather, who barely spoke English when he entered residential school and left school hating his own language and culture. He wanted nothing to do with his heritage, and taught Hill’s mother and her siblings to stay away from the more traditional people in their community. When Hill’s mother met and married a man who had avoided being captured and taken to a residential school (and was raised very strong in tradition), Hill’s grandfather disowned her.

Despite being disowned by her own family, Hill’s mother instilled in her children a desire to be strong and proud of their traditions. Their own people called them “godless pagans,” but Hill and his siblings were raised around those who actually spoke their language and practiced their traditions, so they were fortunate enough to learn.

“Once I was asked by a government minister what the biggest threat I faced was, as an Indigenous person. I decided that WE are our own biggest threat. We’ve been forcibly removed from our identity—and when we don’t know who we are, we’re reckless, empty, wandering souls. That’s pretty uniform across Indian Country. We aren’t comfortable being who we are, and that’s what we need to reconnect with as a people.”

He concluded by saying that often governments try to paint all Indigenous people under the same brush—but from nation to nation and community to community, they’re very different.

“We know how to heal ourselves. I know that. But we need assistance. And this needs to be approached as partners with the governments—not as a father and child type relationship, but as an independent and equal partnership.”

Q&A Session

We see similarities between this issue and the African experience with colonialism, globalism, Christianity, etc. Could you share the methods you use to work against and recover from this?

Hohahi:s-Leroy Hill: Use the tried and true traditions that have been passed down. Apply the experience of generations of teaching from the elders. Connect the youth with traditional knowledge—get them involved in traditional seasonal practices, ceremonies, and rituals. Reconnect them with their identities.

Gerry Oleman: Teach the youth that they come from a beautiful people. Teach them how their people used to live in harmony and sustainability and peace. Give them reference points about who they are outside of the violence and addiction that they’re seeing. Tell them the goodness and impressiveness of the traditions and accomplishments of their people. Get them into ceremony: sweat lodges, fasting, meditation, music. Help them have a good relationship with who they are.

Lori Quigley: Do the work through education. Advocate on state and federal levels for legislation to support teaching native languages in schools, determining our own way of teaching, and sticking with our values. You can’t tell us that our original teachings and ways were “less than.” We need to reverse that story and reverse the trajectory for our youth.

Conclusion

At the conclusion of the meeting, panelists expressed their hope for good change ahead.

“Let’s once and for all say hello to our problems so that we can say goodbye to them. I do believe we are changing and growing. 20 years ago I didn’t. But now I see it, I hear it, I feel it. We can heal, we can unite, we can uplift.”

—Gerry Oleman

Hill closed the meeting with words of thanks for the Great Benevolent One and all the goodness in our lives, offered in his mother tongue from Cayuga Nation, then Bowen ended with thanks for the panelists, attendees, and sponsors of the webinar.

– – –

JoAnne Wadsworth is a Communications Consultant for the G20 Interfaith Association and acting editor of the “Viewpoints” blog.